How To Make Mistakes

A noted pianist recounted an important lesson he’d received in his conservatory days: He and a professor had attended a concert by one of the great performers of the 20th century, a man then nearing the end of his career. Afterwards, the student commented on the number of mistakes the master had made. His professor rejoined: My boy, I’d rather listen to his mistakes than to your best playing.

The professor’s meaning came through loud and clear to the student: The mistakes of a master may have greater merit than the rest of us can achieve with our best work.

I had a glimpse of this truth early in my career—not from an older master, but from a younger one. I was two years out of college when Jim (not his real name), fresh out of MIT, started working with me on a project. At first I was put off by this youngster’s apparent arrogance, but gradually it dawned on me that the guy knew what he was talking about. I began to seek his feedback on my work, and a good friendship developed between us.

Some time after Jim left the company, I told him that I’d been making a bit of a career fixing his mistakes. He was distressed to hear it. No worries, I assured him: he’d made the right mistakes. His work conveyed a good understanding of the problems that he’d been addressing, and was clear enough to help me absorb some of that same understanding. The overall structure was sound; the mistakes were usually in the details.

There was one arguable exception, though: Jim had solved a particularly thorny problem using a very non-traditional approach, which was difficult to maintain after he left. He’d been aware that this unusual technique could become a problem, but he’d concluded that the alternatives would have been worse. Regardless of whether Jim had made the best possible decision at the time, he deserves credit on several grounds: He’d considered different ways to solve the problem; he’d brought the best tools to the job that he could find; and above all else, he’d solved the problem. If his choice was a mistake, it was a mistake well worth making.

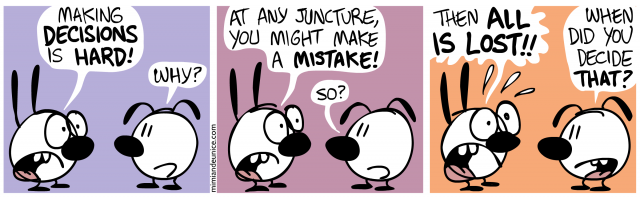

To err is human, or so it’s said. It may be even more human to fear erring. While this fear is often well-founded—it can, after all, save lives—it can also be costly. An excess of caution causes inaction, which often is also a mistake. And as has often been said, every mistake represents a learning opportunity. Since we are all bound to err sooner or later, it follows that we’d do better if we stopped trying to avoid mistakes, and started aiming to make the right mistakes.

Making the right mistakes requires using the right process. In fact, making the right mistakes is all about using the right process; what mistake you make matters far less than how you make it. The better your process for making mistakes, the better your mistakes will be. Drawing upon my vast experience at crafting mistakes, I offer herein some tips that may help you improve the quality of your own.

- Understand the risks. When lives or vast fortunes are at stake, it’s probably not a good time for taking risks. Yet even when the real risks are lower than that, we still carry a severe aversion to mistakes. This can do more harm than good. Many of your mistakes will be forgotten in time; for others, you’ll have chances to make amends. Move your work forward based on what you know, or can learn fairly quickly.

- Define your goals. What are the essential criteria? You and your customers need to agree on these points before much serious work can begin. Beyond the essentials, spend less time analyzing and defining, and more time doing. When choosing between building something good now, or something better later, go for the good. Today’s omissions will be tomorrow’s opportunities, if they are missed at all. Focusing on the essentials will help you respond to requests faster, which will help facilitate the next item on the list:

- Seek feedback early and often. The sooner you discover your mistakes, the easier they’ll be to correct.

- Work consciously. This isn’t some New Age concept, but a very down-to-earth process. Think of it as your personal continuous improvement or Kaizen plan:

- Observe yourself as you work.

- Consider what you’re doing, how you’re doing it, and why you’re doing it that way.

- Look for better approaches. (There’s always a better way. When mistakes are possible, so is improvement.)

- Assess and adjust. Look for your mistakes, take responsibility for them, and learn from them. Don’t let problems fester. Get other people involved, when you need to, but without seeking to assign or dodge blame.

- Make your own mistakes. Understand what’s required. Listen closely to the advice and wisdom that other people have to offer you. But if you think that your best path goes down a different road than the one you’ve been pointed down, then follow that thought. Your successes will be sweeter, and your lessons will be learned more clearly.

There’s a question that’s posed in various places around the Internet:

What would you do, if you knew you could not fail?

That’s too broad for me to answer concisely. (Fix the current economic crisis? Bring peace to the world? Travel in time? My taxes?) Instead I ask myself a slightly different question:

What would you do if you had no fear of making mistakes?

I’d take piano lessons, and I’d write a blog.

One down, and one to go. I think I’m off to a pretty good start.

Update 08 Sep 2011

This is too good not to include here:

Dan,

Welcome to the wonderful (?) world of blogging. My own blog (www.gointothestory.com) is focused on screenwriting, but I’m surprised by how relevant your comments are per someone aspiring to succeed at that craft. Understand risks, define goals, seek feedback, work consciously… those are as relevant to screenwriting as to software writing. Maybe not such a divide or distance between ‘left-brain’ and ‘right-brain,’ eh?

Best of luck. Keep up the blogging. In six months, you’ll be amazed at who you’ve intersected with.

Scott Myers

This is very thought-provoking, Dan. I really loved it.

Hi Dan,

Nice job, and good luck with your blog.

I started a blog last year, http://peterashmathedblog.blogspot.com/. You are invited to look at it, maybe you can learn something. I know I learned a lot from your blog. You are an excellent writer, and a deep thinker.

My blog centers on my career, which is about mathematics education. My posts tend to be shorter and more technical than this one of yours, but I try to be personal, humorous, or philosophical whenever I can slip it in.

I find that I seem to average about one post every two weeks or so, though my posts tend to come in spurts with one a day for a few days, followed by a fallow period. How often do you plan to post?

Peter

Thanks, Peter.

I’m trying to get into a rhythm where I’m averaging close to a post a day, maybe more. I’m also going to be getting more into technical subjects as I go, but I felt that this was a good way to get started.

I had a look at your blog, and nearly didn’t return; you’ve got some very interesting stuff there.

One of the best pieces of advice I got about blogging was that if you can’t post constantly, at least post regularly. That’s the idea behind the Weekly Sift — there’s something new every Monday afternoon.

Readers get discouraged if they come back to your blog and don’t find anything new. Posting regularly helps them get into a rhythm. They think, “Oh, it’s probably time to look at Dan’s blog again”; they look; and — success! — there’s something new to read.

Two thoughts related to mistakes:

(1) Editing is almost always easier than composing. So as a writer, I find I often have to make myself write something that I know is bad, just so I can start editing it.

(2) I’ve developed an appreciation for something I call a good bad theory. It’s bad because it’s almost certainly wrong. But it pulls together all the ideas that you need to think about if you’re going to understand the problem. Using the bad theory gets you thinking in the right terms and paying attention to the right phenomena.

Dan,

I like the blog!

The pianist analogy is a good one. Some of my favorite recordings are live performances by Sviatoslav Richter and it is certainly possible to get past the occasional technical flaws to hear what the performer has in mind. The clarity of his artistic vision is stronger than the technique at times, and it allows the listener to fill in gaps.

– Paul

I finally got around to reading this and it was well worth it. I’m OutofWhatBox on my Google Reader. I know you said your posts get more technical but I’m sure I’ll find value. I’ve always appreciated your thoughtfulness.

Susan

Dan,

1st paragraph says it all.

The reality is that every intelligent effort involves calculated risk, and only two possible results can be expected from every effort: success to varying degrees, and failure to varying degrees.

MIT probably makes one a little less objective, which implies in fact being “in the box” as it goes in the theory of objectivity (a different kind of box here). The idea being that if you have not seen anything in the real life yet and you just finished your MIT studies you must have this sense of knowing it all and knowing it better. Now, by that I don’t mean to say that the MIT is not great, it’s just that the example clearly shows that the real life needs some unboxed MIT skills on top of out of the box thinking. Feel free to ignore what I said, I must still be under the influence of this book:

http://www.amazon.com/Leadership-Self-Deception-Getting-Out/dp/1576751740

-Vitaly

PS

How’s things?

Hi, Vitaly — thanks for the comments. That does look like an interesting book, although it seems to use the term “out of the box” in a completely different way from what I’m familiar with. (I guess they’re making an out-of-the-box usage of “out of the box” 🙂

As for the rest: I’m sending you an email.

Its an out-of-the-box read indeed. It will discover how much in the box the reader was never even suspecting about it. And guess what there will be no one who can claim to be “completely” out of the box after reading this book. It will also explain why people behave the way they do. You will be able to tell what was going on with that person who blew up all of a sudden for no apparent reason..guaranteed.

There is also another one to read while on vacation: “Mindfulness” by Ellen Langer PhD.

PS don’t try to use the out-of-the-box concept with people not familiar with it – unexpected side-effects can occur 🙂

[…] really enjoyed this post by Dan Breslau, on “how to make mistakes.†I especially enjoyed his question, “What would you do if you had […]